William Brumfield’s Time Machine: Nous, Tekhne, and the Human Eye

Preface:

I wrote this piece because Bill is not only a towering scholar, he is my friend. He has been a steady mentor to me here at Tulane, the kind who answers a quick question with a story that opens three new doors. I have kept up with his many books for years.

This article grew out of our commute chats after work, the kind of rolling conversation you only get in a car with the same route and too many ideas. Bill talks about churches and towns the way some people talk about family.

Since this runs in my Hooked on AI newsletter, I had to connect the dots to today’s tools. The connection is not a gimmick because it sits at the heart of the work. Photography, done the way Bill does it, is dated, placed, and accountable. It lets you test a claim against time. AI, done responsibly, can help us sort, compare, and surface patterns in that record. The tools can be useful, but they do not decide where to stand or when to return. That judgment is human.

A lot of creative people feel insulted or pushed aside by the pace of AI. I get it. Fear of irrelevance is honest and history gives us some grounding on how world changing new and emergent technology is on society. Painters worried when cameras arrived, but ainting did not die. It changed. Photography did not steal its soul. Instead discovered its own and become it's own seperate and distinct artform. We are in another of those hinge moments. The answer is not and can not be retreat (considering that retreat isn't an option provided to us anyway). Instead, the answer is clearer authorship and better craft.

Bill’s work shows what that looks like in practice. He dates the frame, records the vantage, and returns to the same ground years later. That discipline carries both mind and craft. If you like old terms, call it nous and tekhne (Bill's personal analogy of what he does). The first chooses and judges and the second executes with care. AI may help our tekhne scale, but it will not give us nous.

So this essay is a thank you to my friend, and a small field guide for anyone trying to make peace with new machines without losing the human center. If you finish it with a plan to stand somewhere specific, at a specific time, and look hard enough to write an honest caption, then we are on the right road.

Enjoy the article, and say a quiet thanks to the man who kept going back.

--

Photography keeps time honest. That is the quiet thesis of William Craft Brumfield’s life’s work and it is the promise his pictures keep for anyone willing to look with intention. Brumfield is a Tulane scholar of Russian culture who has spent more than five decades returning to the same streets, the same thresholds, the same towers and domes across the Russian landscape. He records the date, he marks the vantage, and then he comes back. The result is a method: a disciplined practice of seeing that treats photographs as evidence and as arguments at once.

From a distance the habit looks simple. Put the camera where it needs to be, write down when you were there, repeat. Inside that habit sits a philosophy of visual literacy that many scholars only nod toward. A picture is not a loose illustration for a text. It is its own form of knowledge, and it only becomes knowledge when the frame is anchored in time and intention. That is why Brumfield insists on the date, the vantage, and the return, and why he bristles at image use that ignores when and how a thing was seen. He is wary of the floating, unmoored photograph that flatters the eye and cheats the mind.

The discipline of the dated frame

Brumfield’s recurring lesson is that a precisely dated photograph expands thinking instead of closing it down. Once you know when the shutter clicked, you can ask what had to happen before that instant for the scene to exist as it does. You can ask what followed. A fixed moment becomes a sliding scale. The historian can move backward to causes and forward to consequences because the picture has a known address in time. That sliding scale is the difference between a definite moment and a defining one. There are infinite definite moments. Defining moments occur when a trained eye and a trained mind meet a subject in a way that clarifies more than it merely captures.

Photography is the closest we have to time travel. It freezes one instant, yet it prompts a cascade of questions about what preceded and what followed. Even a single still can send you backward into the making of a building or forward into the fates of its caretakers. When you return to the same site and make a new photograph, you create a checkpoint, a measurable way to ask what changed between then and now and why.

The camera in this practice is not a neutral recording device. It is an extension of the person who carries it. The position is literal, where the photographer stands, and intellectual, what they want the subject to reveal. Brumfield’s work leans into both senses, rejecting the idea that the photographer is a passive automaton. He chooses his ground and frames with a purpose. He refuses the drone’s circular pan in favor of a vantage that makes the building legible.

The human vantage

Humans do not think in ones and zeros. We think in images and abstractions, then we translate those into words. That is why the photograph often feels closer to how we actually remember than a paragraph does. Say a cathedral’s name and your mind assembles color, scale, angle, light. The machine thinks as numbers. We see as forms. A good photograph bridges that gap without pretending the bridge is effortless.

This is where craft lives. Brumfield’s choices about light, angle, focal length, and season are not technical flourishes for their own sake. They are the means by which the structure’s truth becomes visible to someone who was not there. You can, of course, build a perfectly exposed, glassy picture of a façade that teaches nothing. You can also accept a grainy or oblique picture that reveals the way a roofline floats or how a drum sits on its base. The right picture is the one that clarifies the subject’s form and meaning for another mind. The camera becomes a continuation of the eye, and the eye is informed by books, archives, maps, and the memory of earlier visits.

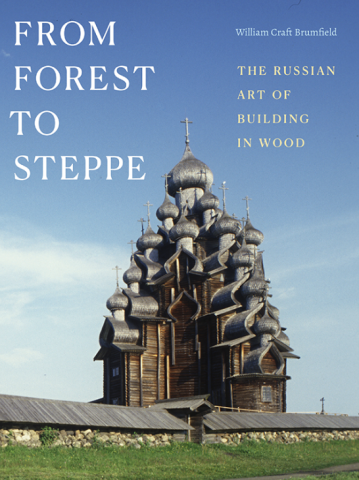

Brumfield’s corpus is rich in churches and monastic ensembles, especially in the North where wood meets weather and endurance acquires a spiritual charge. Churches are never only religious buildings. They collect politics, ritual, local identity, and family memory. They are scarred, rebuilt, neglected, restored. Photographing them across years makes those layers legible. The same dome teaches different lessons once you know what was lost and what was repaired.

Two notes from the photographer

By presenting precisely dated photographs over a period of almost five decades, the book is not the product of an "assignment" but a unique project composed retroactively and informed by the photographer's path as a scholar. The buildings through these photographs are re-contextualized.

Photography has a uniquely integral relationship to architecture, with its three dimensions (four in that buildings change over time). With the registering of depth and shadow, the photographer has infinite possibilities, directed by technical knowledge, to (re)present the structure, to interpret it. These possibilities are there to be shaped by the photographer's knowledge.

Art, in the richest sense, is a meeting of mind and craft. Or as a useful shorthand: ART combines classical Greek concepts of nous and tekhne. Nous is the discerning intelligence that chooses a vantage and recognizes meaning. Tekhne is the practiced know‑how that turns light, glass, shutter, and sensor into a faithful presentation. Brumfield’s photographs come from that meeting. The choices are intellectual before they are mechanical, and the mechanics only matter because the mind has already decided what the picture should teach.

Definite and defining

Henri Cartier-Bresson popularized the idea of the decisive moment. Brumfield’s vocabulary is adjacent but distinct. For him there are definite moments, the infinity of instants a camera can arrest, and defining moments, the rarer frames in which judgment and form align. Critics and historians affirm those images over time. The definition does not come from a museum label or a social feed. It comes from how persuasive the photograph remains as new information accumulates. You can test this by returning to the same place and making another picture from the same ground. If the first frame continues to teach alongside the second, it was probably defining. If it collapses into mere decoration when set against later knowledge, it was probably only definite.

Brumfield explains this logic crisply when he speaks about dating. The date lets the photograph serve as a temporal slide rule. You can move backward to a structure’s design and funding, to who lived near it, to what it replaced. You can move forward to wars, policies, restorations, disasters, neglect, enthusiasm. All of those are brought into a relation by the simple discipline of the dated frame and the recurring return.

Institutions and the long view

Attention like this attracts caretakers. Over the years major cultural institutions have recognized the value of Brumfield’s archive and helped it find durable homes. The Library of Congress supported his work in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The National Gallery of Art began collecting his photographs in the 1980s. Those placements matter because they keep the pictures in conversation with catalogues, maps, and the other tools scholars need to put images to work.

The institutional story also hides a simpler truth. A collection is a promise. It promises that the pictures will not be lost and that their captions will be preserved. It promises that a researcher will be able to place one view against another and trust what the comparison shows. Brumfield’s photographs repay that trust because they were made with scholarship in mind. The notes and dates are precise. The vantage points are deliberate. A cataloger does not have to rescue the pictures from vagueness.

Nous, tekhne, and the age of models

This is the Hooked on AI newsletter, so we have to face the obvious question. What happens when a world full of cameras meets a world full of models?

Start where Brumfield’s practice points. Nous and tekhne do not pull in the same direction by accident. Nous chooses. It judges when to return, which angle clarifies structure, which light makes volume honest, which caption keeps a reader from getting lost. Tekhne executes. It stabilizes a handheld frame in wind, exposes for snow without lying about tone, and produces a file that still holds detail when printed large. AI extends tekhne. It can index at scale, cluster variants, register repeat shots, summarize captions, translate place names, and surface patterns hidden in thousands of frames. Useful, real, and measurable.

But nous is still human. A model does not take responsibility for a point of view. It does not feel the obligation to stand where a building becomes legible to a stranger. It can propose, interpolate, even invent. It cannot care first and compute second. That is why Brumfield’s discipline of dating, returning, and re‑contextualizing remains the core of the work. The archive can be activated by AI, but it is authored by nous.

Once you see the split, the roles become clearer. Computer vision can register small changes between two photographs from the same vantage, signaling structural movement or weathering that a casual viewer might miss. Embeddings can group related motifs across a corpus, gathering, for example, every instance of a particular brick pattern or cornice profile. Language models can draft alt text at scale to improve accessibility, then stand back for expert correction. None of that chooses where to stand or when to press the shutter. The model does not know what the building is trying to say.

Walter Benjamin’s old argument about mechanical reproduction is still useful here. Reproduction detaches art from a singular presence in time and space. Digital images accelerated that. Generative systems push it further by creating pictures with no originating subject. Brumfield’s practice offers a counterweight. By insisting on return, date, and context, he thickens the aura rather than thinning it. Each new visit adds another layer of encounter with the same structure. The presence deepens because the attention deepens.

Above the abyss

Brumfield sometimes frames this work with an image of standing on the lip of an abyss. Time and entropy will erase any moment that a camera can arrest. That is why the dated photograph can feel like a rescue without pretending to be salvation. The point is not to freeze a world for the sake of nostalgia. The point is to make a reliable place to stand and think. When he sets his pictures next to the early color images of Sergey Prokudin‑Gorsky, you can feel that reliability at work. The century between them becomes legible. What persisted becomes visible. What changed becomes instructive.

Call this a pedagogy of attention. It teaches patience, the patience to return and to compare. It teaches humility, the humility to admit that a building can be looked at in many truthful ways and that one must pick a vantage that helps another person learn. It teaches courage, the courage to say that a picture is more than décor and that captions should tell the truth even when the truth is messy.

Why this matters

In a culture that skims, it helps to have work that refuses to be shallow. Brumfield’s photographs are careful on purpose. They make claims you can test. They carry dates you can verify. They welcome comparison. They are generous to future scholars who have not yet been born, to local historians who will need to settle a neighborhood argument, to restorers who must decide how a roof line once met its drum.

The stakes are not parochial. Russia’s architectural patrimony is large, various, and contested. Much of it is fragile. Buildings remember what people forget. A century from now, the existence of a dated picture from a known vantage could be the difference between guesswork and understanding. That is the practical edge of what can sound like a romantic vocation.

There is also a moral edge. To look well is to accept a duty to describe well. To return is to accept a duty to learn. To date a frame is to accept a duty to tell the truth about when you saw what you saw. These duties are small compared with the powers now available to any phone, any software package, any model. They are also the reason that the models are useful rather than corrosive. If nous and tekhne keep their order, the tools can be allies. If we reverse the order, we end up with impeccable fabrications that teach nothing.

The buildings change. The method endures because it honors both halves of art, nous for judgment and tekhne for craft, in that order.

Coda: back to the ground

Before you close this window, pick one place you know well. Find one dated photograph of it that you trust. Stand where the photographer stood and make another picture with the same horizon and the same angle. If you cannot stand there, place the two pictures side by side and ask what happened between them. What changed. What survived. What the structure learned. Then imagine doing that for a lifetime, across a continent, with the care of a scholar and the stubbornness of an artist. That is what William Brumfield has been up to. And that is why his pictures are not a hobby or an ornament. They are a time machine that anyone can use, provided they enter with nous, and leave room for tekhne to do its honest work.