World Models: When AI Stops Guessing and Starts Imagining

As every tech wave matures, one idea usually hogs the spotlight for a while. In edtech it was gamification, then “flip the classroom.” In data science it was big data, then data lakes, then blockchain. The pattern is familiar: a new capability becomes possible, everyone pivots their slide decks to talk about it, then it settles into the stack as one layer among many.

AI is going through the same kind of phases. First we just wanted a chatbot that did not embarrass itself. Then attention and large language models took over the conversation. Then we pushed on chain of thought prompting to stretch reasoning, retrieval to keep answers grounded, tools so models could call calculators and APIs, and full agents that run semi-autonomous workflows. On top of that, we got connector layers like Anthropic’s MCP, the “USB-C for AI,” that let models plug into existing infrastructure.

None of those are fads. They are stepping stones. They made models more useful, more connected, and more embedded in real systems. I think the next big hill, not the final one but the next one we have to climb, is world models: AI systems that carry an internal simulation of how parts of the world change over time. To make that shift concrete, here is a side by side comparison.

---

Picture a small robot dog in your living room.

You want it to walk from the door to the couch without clipping the coffee table, trampling the LEGO minefield your nephew left behind, or sending the cat into low orbit. You could let it learn by trial and error in the real room, one clumsy crash at a time, the way toddlers discover gravity. Or you can give it something stranger: its own tiny version of your living room inside its head.

In that inner space, the robot practices thousands of runs without touching a single table leg. It tries weird paths. It bumps into invisible furniture, rewinds like an old VHS tape, and tries again. Only when it has gotten halfway competent does it enter your actual house, where the cat waits with skeptical eyes.

That inner space is the heart of a world model.

A world model is what you get when an AI stops treating the world as a series of disconnected inputs and starts building an internal, working sketch of how things change over time. It is something more modest and more practical than “intelligence” in the grand philosophical sense: a learned pocket universe the system uses to imagine what comes next.

Think of it as giving a machine the ability to daydream.

---

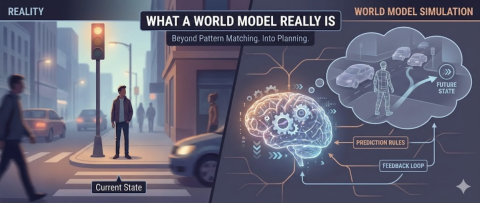

What a World Model Really Is

The easiest way to understand world models is to start with yourself.

When you cross a street, you do not calculate physics equations. You have an instinctive feel for how fast cars usually move, how long they take to stop, how quickly you can walk, and how likely that driver staring at their phone is to notice the light turning red. You run a little simulation in your head. A private movie of what happens if you step off the curb now versus three seconds from now.

That simulation is your world model of streets and cars and you.

In AI terms, a world model is any internal picture that lets a system do three things. It keeps track of what is going on. It predicts how things might change. And it uses those predictions to choose an action.

The models can be very simple. One might predict the next frame of a video from the previous frames. Another might predict where a robot arm ends up if the motor turns a little more. A third might predict the next game state in chess when you move a piece.

The focus is on continuity rather than perfection. The system has a sense of before and after, and it can run that movie forward in its head instead of waiting for reality to do it for real.

That is the key shift. Old style systems mostly reacted. World models let systems rehearse.

---

How World Models Move Beyond Fancy Autocomplete

Most people meet AI through text and images. You type something and get a reply. You upload a photo and get a caption. It can feel impressive but also hollow, like chatting with a very well read parrot that has memorized the encyclopedia but cannot tell you where it left its keys.

Those models are mostly doing pattern completion. Given this prefix, what comes next. Given these pixels, what label fits.

A system with a world model behaves differently.

It keeps a state in mind. A compressed representation of the situation right now. Then it learns rules for how that state usually changes. That lets it ask questions a pattern matcher cannot. If I do X, where do I end up. If I wait instead, what happens. If something unexpected occurs, what does that imply about my previous assumptions.

Suddenly you are planning as well as autocompleting.

Imagine a warehouse robot that needs to move pallets around workers, forklifts, and surprise obstacles. A pattern matcher can say this looks like a forklift. A world model can say forklifts tend to turn here, which means the space near that corner will probably be blocked in a few seconds, so I should not route myself through there.

Same sensors. Same world. Different kind of thinking.

---

What Lives Inside a World Model

Underneath the buzzwords, the ingredients are fairly simple. You can think of a world model as having three pieces, like a simple machine made of gears and springs.

First, it needs some compressed description of the world at a moment in time. For a game, that might look like positions of all the pieces plus the current score. For a robot, it might be joint angles plus a rough map of the room. For a tutoring system, it might be what this student likely understands and where they struggled last week.

Second, it needs learned rules for how that description tends to change. If the ball is here and you kick it that way, it ends up there. If the student got three fraction problems wrong in a row, their probability of understanding fractions probably dropped. These are patterns the system absorbed from a lot of examples rather than hand written rules, the way you learned to catch a baseball by catching a baseball, not by studying trajectories.

Third, it needs a way to check itself. The model predicts what will happen, reality serves up what actually happened, and the difference is used as feedback. Over time, the internal little universe gets nudged closer to the real one, at least within the slice of reality the system cares about.

Humans do something similar. Your inner model of how your boss reacts gets updated every time you bring surprising news into their office. You walk in with a worry about budgets and their face tells you whether today is a reasonable day or a day to retreat quietly and try again tomorrow.

---

Where You Will Notice World Models First

Most people will never read a paper about model based reinforcement learning. They will just notice that some tools suddenly stop feeling quite so clueless.

Robots are the most obvious place.

Instead of programming them for every small motion, or letting them experiment in the real world like toddlers with steel fists, engineers can let them learn in a simulated space first. The robot tries thousands of ways to pick up a plate, or fold a towel, or walk up a staircase its designer has never seen before. All of this happens in a synthetic room where gravity still works and physics still applies but broken plates cost nothing.

Once the simulated practice looks good, only then does the real machine try the move. It will still make mistakes. Just fewer, and usually gentler ones. That is the power of rehearsing in an internal world instead of discovering gravity by dropping your fiftieth plate while your human supervisor watches with growing alarm.

Digital assistants are another good example.

Most assistants today behave like they have amnesia. You ask for help planning a trip, then later you mention the conference, and they act like they have never heard of it. With a world model behind them, an assistant could maintain an internal picture of your projects, constraints, and likely future states. It could track not just what you said but where you seem to be headed.

It sees beyond “meeting at 3pm.” It might see if you accept one more weekly meeting in this slot, three important tasks will consistently get squeezed to your evenings, and you will start each morning already tired. It can simulate different calendar arrangements and suggest ones that keep you from burning out.

You would still choose your schedule. The difference is that you would see it as one option among many simulated ones, instead of the only pattern you stumble into because you said yes too quickly at the wrong moment.

Then there is science.

A good world model can stand in for expensive or dangerous experiments. Instead of physical prototypes for every idea, you have a learned simulator trained on past experiments and data. You design a drug, a material, a climate policy, or a new transit system, and the model plays out what is likely to happen if you commit. It shows you the version where it works and the version where it fails in some unexpected way you would not have noticed until year three.

Instead of one design, one test, and months of waiting, you explore many options virtually, then build only the few that look promising. This provides a much better starting point without removing the need for real world testing, the way a dress rehearsal lets the actors find the awkward bits before opening night.

---

Everyday Uses: How This Touches Normal Life

It is easy to leave this at good for robots and scientists and move on. In practice, world models will show up in more quietly personal ways, the kind of tools you notice only after they have been around for a while and you cannot quite remember what life was like without them.

A tutor that has worked with you for a while can build a model of your learning trajectory. This includes how quickly you usually pick up new ideas in this subject, which distractions derail you, and which explanations tend to click, as well as what you got right or wrong yesterday. Maybe you learn better in the morning. Maybe you need three tries at a concept before it sticks. Maybe certain kinds of praise help and other kinds make you self conscious.

Now the tutor tests different future paths in addition to quizzing you. If I push harder now, they might get frustrated and quit. If I give one more easy problem first, they might settle in. It runs those options internally, silently, then chooses the path that keeps you in a zone where you are challenged but not crushed.

Financial planning is another good candidate.

Instead of a generic conservative or aggressive profile based on your age and a questionnaire you filled out in ten minutes, a system can learn a model of your personal life arc. Your income volatility. Your dependents. Your goals. It explores what happens under different combinations of job changes, health events, caregiving roles, and policy shifts. It sketches a landscape of likely futures the way a weather map shows different storm tracks, though it cannot predict the actual future.

That lets you ask questions like what does my savings situation look like in ten years if I take this job with more travel and less pay. What happens if I move states, given the local cost of living and my current risk tolerance. What does retirement look like if I keep working this hard versus if I downshift now and stretch the timeline.

You still make the call. The system serves as a simulator of consequences, a way to test the weight of choices before you lift them for real.

Health care might see similar systems. These would focus on pattern watching over time rather than instant diagnosis miracles, which is where everyone’s mind goes and where the disappointment usually lives. A model that learns your personal baseline can simulate how different choices might affect the next few years of your health, based on streams of data rather than a single lab result taken on a day when you were stressed and had skipped breakfast.

Used well, this supports doctors with an extra pair of eyes that never sleeps and can scan over entire patient histories in one pass, instead of replacing them. It notices the small drifts and trends that get lost when you only see someone twice a year.

---

Why World Models Are Exciting

There is a reason researchers get so animated about this topic, the kind of animation that makes them talk faster and use their hands more. World models are one of the clearest paths from chatty pattern matcher to system that can actually help think about consequences.

One obvious upside is better decision support. Humans are not good at holding large branching futures in our heads. We fixate on one or two scenarios, usually the scary ones, and then argue from those. We forget the middle paths. We ignore the quiet disasters that happen slowly.

A good world model can give you a menu of plausible futures instead of a single hunch. That widens the space you are thinking inside, even if it does not guarantee wisdom. It lets you see the paths you were not considering because they did not occur to you or because they seemed too complicated to imagine all the way through.

Another benefit is safer exploration in domains where failure is costly. You would like an autonomous vehicle to make most of its mistakes in simulation, the version where crashed code does not mean crashed metal. You would like a pandemic response policy to be tested in a virtual population before it is tried on a real one. You would like the nuclear reactor design to fail a few thousand times on a screen before anyone pours the concrete.

There is also a creative upside, which is less discussed but maybe more interesting in the long run.

Writers, game designers, teachers, and artists can all use world models as partners. Imagine a story engine that has a sense of narrative cause and effect, so when you make a choice for a character it can say follow that choice and the tone of this book will drift into tragedy by chapter ten, or this plot thread you introduced in chapter two will never pay off and readers will notice. You then get to decide whether that is the path you want, or whether you need to plant something earlier to make the ending feel earned.

The same idea works for course design. A teaching model can suggest how different module orders might play out for different kinds of students, then flag likely dead spots or overload weeks before you ever run the class. It might notice that if you put the statistics unit here, students who struggled with algebra will hit a wall, but if you move it two weeks later after they have done more practice problems, the success rate climbs.

In all of these cases, the system generates a richer playground of what if rather than dictating the answer, and humans choose which branch is worth trying in the real world.

---

The Risks of Living With Synthetic Worlds

Of course, any tool that can make realities feel more vivid can also make illusions more convincing. That is the trade. Brighter light, darker shadows.

One obvious problem is simple wrongness. A world model is only as good as the data it has seen and the feedback it gets. If it was trained on partial, biased, or outdated information, it will happily simulate a future that does not include entire groups of people, or misjudges certain risks, or exaggerates others.

Those blind spots can be quiet and systematic, the kind of errors that do not announce themselves. The model might consistently undervalue long term environmental costs because the underlying data treated them as externalities. It might treat certain neighborhoods as less important because the training data came from city plans that already dismissed those areas. Now the simulation shows optimal plans that are neatly aligned with those old biases, and the wrongness has the shine of mathematics on it.

There is also the persuasive power of seeing it play out.

If a policymaker or CEO can sit in front of a dashboard that animates the future for them, it is very easy to forget that the underlying world is still a model. The person who chose the parameters and tuned the system has a lot of influence over which futures look responsible and which ones are made to look reckless. You can tilt the gravity of a simulation just by deciding what gets weighted more heavily, what risks get flagged in red, what benefits show up in green.

You can imagine these tools being used to rationalize decisions that were already made for other reasons. The model says this is the only realistic choice, when in reality the model was trained and configured by people who already preferred that outcome. The simulation becomes a kind of authority you can point to, the way people used to say the data shows when what they meant was I want this and I found a chart that agrees with me.

On a more personal level, you can also imagine people getting lost in simulation, the way you can lose an afternoon scrolling through old photos or alternate versions of your life on social media.

A personal digital twin that can show you a thousand slight variations of your life is intoxicating. Here is the version of you who moved to another city. Here is the version of you who stayed. Here is the version who took the risky job or walked away from it. Here is the version who said yes to the relationship and the version who said no and the version who said yes but at the wrong time.

In moderation, that kind of exploration helps with reflection. It lets you test choices in your head the way you might talk through options with a friend. At the extremes, it can make real life feel like the disappointing branch, the version that runs too slowly and glitches in boring ways, where the lighting is wrong and the dialogue does not snap.

We already see pieces of that in gaming and social media. More responsive, more personalized world models will crank the intensity up. They will make the simulated worlds feel more real than the world outside your window, and that is a strange place to live.

---

A Simple Way to Judge Any Use of World Models

You do not need a PhD to have a grounded opinion about world models. A short checklist is enough to start asking good questions, the kind that make people uncomfortable if they have been sloppy.

Whenever you hear that a system simulates scenarios or uses a world model, ask these. What slice of the world is it actually representing. Where did the data for that slice come from, and who was missing. Who chooses the knobs, and who gets to see the outputs. What decisions are being made in the real world based on those simulations.

If those questions get honest, specific answers, you are at least in the right ballpark. If the answers are vague, hand wavy, or secretive, be cautious about how much weight you give the simulated futures on the screen. Treat them the way you would treat advice from someone who will not tell you where they got their information.

---

A Little Futurism: Worlds Inside Worlds

If you push this idea out a decade or two, you end up in a landscape where many institutions, and many people, have their own running simulations. Not as a luxury or a novelty, but as a basic tool, the way we now carry maps in our pockets and think nothing of it.

A city might keep a live world model of itself that is continually updated from sensors, public records, economic data, and citizen input. Planners could ask what if we put a light rail line here, and the model would spin forward changes in traffic, air quality, rents, where people choose to live, what businesses move in or out. Activists and community groups could ask their own questions of the same shared model and challenge the results. Everyone works from the same simulation but argues over which futures are desirable.

Families might carry around personal models that help them plan care for aging relatives, or manage chronic illness, or juggle two careers and children without falling into permanent exhaustion. Not as a replacement for talking to each other, but as a tool for thinking through scenarios when the stakes are high and the options are complicated. What happens if we move Mom closer. What happens if we hire help. What happens if one of us cuts back to part time for two years.

Researchers might plug domain specific world models into one another, building compound simulations. A climate model speaks to an economic model, which speaks to a social stability model, which speaks to a migration model. Together they generate candidate policies that are less naive than any single model alone. Humans then fight over which ones are acceptable, which is the part that never goes away. The simulation does not remove conflict. It just makes the conflict more informed.

There will also be purely playful versions. Synthetic worlds built mainly for exploration, storytelling, and games. The interesting twist is that as world models get more capable, the line between serious planning tool and very sophisticated game starts to blur. A simulation that began life inside a city planning department might leak into education, entertainment, and art. You could walk through the city that never was, the version that got voted down in 2031, and see what you missed or what you avoided.

At that point, we will be living with overlapping imagined worlds, some tuned for fun, some tuned for caution, some tuned for persuasion. You will move between them the way you now move between apps, and you will have to remember which one you are standing in.

---

Where This Fits in the Bigger AI Story

From the point of view of someone writing about AI for the long term, world models are a durable concept. Models will come and go. Brand names will change. Benchmarks will be broken and forgotten. The idea that powerful AI systems build internal, evolving maps of the world is not going anywhere. It is too fundamental. Too close to what thinking actually is.

That is the hinge where a lot of the interesting questions live.

When machines can rehearse futures, how do we use that capacity without handing over control. When they can simulate us, how do we prevent those simulations from quietly defining what is normal or acceptable. When they can absorb more data than any person ever could, how do we keep human judgment at the center of choosing which imagined worlds we actually try.

World models represent one piece of intelligence, human or artificial, rather than the whole. But they are the piece that turns raw pattern recognition into foresight, and foresight is where the leverage is.

If today’s systems are very fast mirrors, tomorrow’s world model based systems will be more like very fast daydreamers. They will spin scenes, test paths, and present us with previews. They will show us futures we would not have imagined on our own and futures we wish we had not seen.

The hard part is deciding which previews we treat as warnings, which we treat as inspiration, and which we politely ignore while we walk out into the real world and do something else, rather than the building of the models themselves. That has always been the hard part. The machines just make it more vivid.